Shutterstock/M-SUR

Russian propaganda in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary

Since the illegal annexation of the Crimean Peninsula and the start of the conflict in eastern Ukraine in 2014, relations between Russia and the West deteriorated significantly. As was repeatedly proven, Russia continually tried to apply various tools to distract, dismay and divide Western allies. One of the most frequently discussed means is using various forms of propaganda (including disinformation) to manipulate audiences in Western and Central Europe.

The aim of this article is to briefly explain the variety of propaganda tools and techniques of manipulation applied by Russia, particularly in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia, and then to describe the perception of Russia in those respective countries.

Russian propaganda tools

The significant mobilization of Russian assets and the polarization of the debate about geopolitical issues allowed researchers to map the actors articulating pro-Russian narratives quite accurately in the course of the past years. Generally speaking, there are three types of channels used by Russia to spread propaganda: official news agencies, so-called alternative platforms, and local political actors. In the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia all three tools have been employed.

One example is the website Sputnik CZ (a branch of the Russian information agency Sputnik) that was officially established in 2014 and that targets Czech and Slovak audiences. The website presents a one-sided interpretation of world events, provides unlimited space for statements of Russian state officials, and generally aims to promote a positive image of Russia. To do so, it also uses disinformation and biased reporting, such as for example gross exaggeration of the number of participants at demonstrations related to the placement of an explanatory sign to the statue of Soviet Marshal Ivan S. Konev in Prague in 2017.

In Hungary, while there is no official Russian state media present, the highly-centralized nature of the Hungarian media space under the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orban means that mainstream pro-government outlets closely follow and disseminate pro-Russian messages. These narratives even include major Russian conspiracy theories, such as the 2018 piece published in the main daily newspaper Magyar Idők (now Magyar Nemzet), portraying the Ukrainian Maidan revolution to be a “CIA executed plan of George Soros” to install a “puppet government”.

Similarly, in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, many websites, blogs and Facebook pages have been established in the past few years, that are prone to spreading conspiracies and anti-democratic messages. One example is the online discussion following the Kerch strait incident in 2018.

The other channel of Russian propaganda – pro-Russian sympathizers – are a heterogeneous group comprised of pan-Slavic nostalgics, right-wing extremists and political pragmatists, who often occupy leading political/institutional positions, and try to win over the favour of the Kremlin. The most noteworthy example is Czech president Miloš Zeman who repeatedly advocated pro-Russian positions. Some of his advisors are known to have close connections with Russian entities.

Russian Fanboys and Westernisers

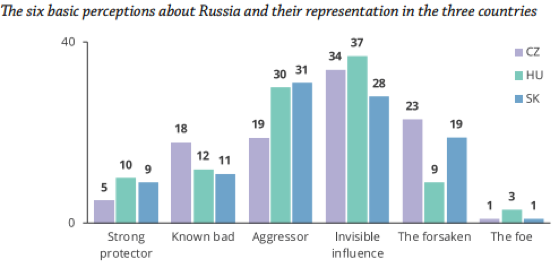

But how do the Russian attempts actually resonate in the public debate?Together with Bakamo.Social, we conducted a big data research of millions of grassroots communications in the form of online articles, comments and social media messages in order to better understand basic sentiments, perceptions and ideas related to Russia. When it comes to basic sentiments, Russia is regionally mostly perceived as either being an “aggressor” (on average 26.7%) or an “invisible influencer” (on average 33%) in our sample.

Conversations of Russia being a ruthless, unpredictable military power or a manipulator were driven by stories about the 1940 Katyn massacre in Poland, the invasion of Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968, Crimea in 2014, and the 2016 US presidential election. Based on these perceptions we successfully identified six types of consumer profiles of people who tend to follow Russia-related news.

Among those who view Russia favourably, “Russian fanboys” resonate to Russian militarism and masculinity, “Russia pragmatist” to mutual trade deals and interests, and “Russia admirers” to Russian high culture and Soviet nostalgia. Anti-Kremlin groups consisted of those who support Western integration (“westernisers”), who are “scared of Russia”, or exhibit distrust towards both the West and the East (“suspicious people”). The common thread connecting all of these perceptions and consumer groups were core messages that could be traced back to strategically disseminated disinformation and information campaigns related to the Kremlin, which tried to make Russia or the Kremlin look bigger, better or stronger in the international arena.

Slovak/Czech Pan-Slavism and the Hungarian “Eastern opening”

Although the majority of the grassroots communicated were anti-Russian in all three countries, Slovakia proved to be the most pro-Russian, followed by Hungary and the Czech Republic. In Slovakia, research results revealed 28% having positive sentiments towards Russia, which had to do with Russia-related news disproportionally covered by pro-Russian disinformation sites, and with far-right and paramilitary groups cherishing historical Pan-Slavic ties between the two countries.

Hungary’s second place was somewhat a novelty given the historical animosity of Hungarians towards Moscow, based on the 1848 and 1956 revolutions crushed by Czarist and Soviet armies, and the lack of significant cultural or linguistic ties to Russia. The fact that only 52% of Hungarians expressed a negative sentiment towards Russia as compared to 65% of Czechs could be explained by the Hungarian government’s and the Fidesz elite’s deliberate pro-Russian or pro-Eastern turn and Euroscepticism after 2010, expressing a strategic interest in developing strong diplomatic, economic, and later cultural ties to the Kremlin. This turn was amplified by Russian official websites as well as disinformation sites.

Hungarian fringe sites expressing a pro-Kremlin geopolitical orientation (and mainstream government-controlled outlets) thus echoed the Hungarian Prime Minister’s conspiracy theory about George Soros’ plan to end the nation states and his praise of the Kremlin for withstanding “the Western attempts of isolation and regime change”, while stressing the need to form a strong bond with Russia on economic grounds related to international trade and the energy supply of Hungary.

In the Czech Republic, negative sentiments towards Russia were identified, which is not surprising when considering the strong resonance of memories of the 1968 Soviet invasion in public discourse, the stereotypical perception of Russia as a culturally, economically and socially backward country, and the intense debate about the current Russian behaviour on the international stage.

This mixture of negative sentiments makes Czechs more resilient towards Russian propaganda, but it also backfires since the topic of relations with Russia is becoming an instrument in domestic political struggles. The internalization adds more emotion to the debate, which in some cases leads to an attempt to label all undesirable events as (at least partially) resulting from Russian malign actions.

Paradoxically, the fear of Russia does not result in an attempt to secure the country’s position as a reliable partner in Western institutions. This is highlighted for example by the low level of support for EU membership (according to Kantar survey from April 2019 one third of Czechs support leaving the EU). That being said, there are still Russia sympathizers among Czechs, who can be divided into two groups: nostalgic people adoring the Pan-Slavic unity and the Communist era, and newly emerged conservative populists refusing the liberal values of Western societies.

Real vulnerabilities

As was shown, Russia utilized various channels in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia to promote its narratives. The research shows that there are certain groups present in the three countries that are sympathetic to those messages – mainly people nostalgic of the Communist past and right-wing populists with anti-liberal views.

It is necessary to place their views in the context of the current uncertainty and identity crisis that is present in the countries that were analysed. In many Central and Eastern European societies, the integration into the West after the fall of Iron Curtain was not perceived as a great success story by everyone. Instead, those societies increasingly perceive themselves as inferior and alienated from the West, which makes them more prone to Russian propaganda. Hence, the main challenge is to find a new narrative that helps Czechs, Hungarians and Slovaks overcome this moment of uncertainty and reaffirm their bond with Western institutions.

Jonáš Syrovátka is a Program Manager at the Prague Security Studies Institute focusing on disinformation (mainly in the context of election campaigns) and strategic communication. He is also researching the development of the Russian political system and its history as part of his doctoral studies at Masaryk University in Brno.

Lóránt Győri is a sociologist and political analyst, with a masters in social sciences from Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, where he is currently working as a geopolitical analyst for the Political Capital think-tank on issues such as Russian soft power, disinformation, and populism in Europe.

Comments

* Your email address will not be published